Noise Pilot: Giving Artists Control Over Iterative Diffusion

James Smith, CS 280A, Fall 2024

Introduction

Diffusion models such as Stable Diffusion [13] or DALL-E [14] allow people to create detailed digital images user natural language prompting. The user types a text description of what they want the image to look like and the machine learning (ML) model attempts to create it. If the user doesn't like the output, they simply need to change the text description they provide the model in a process known colloquially as prompt engineering.

It turns out prompt engineering is difficult and people aren't very good at it [20]. Theories as to why range from prompt engineering as being a skill that we haven't developed yet, to natural language specification being ill-suited to describe to describe a complete creative output.

Artist workflows typically do no resemble this process. Creation is an iterative process where the user comes up with an idea and attempts to produce that idea through interaction with a medium. As they perform this interaction their ideation continues and informs further actions in the medium. This is a process known as material interaction [15]. Engaging in material interaction often changes the direction the artist wants to take the creative work. It is currently not known whether or not prompt engineering fully embodies this practice, but artist reactions to generative AI taking too much control of their artwork suggests that a more fine grained approach may support them better.

We propose Noise Pilot, a tool which addresses this problem directly by giving digital artists more direct control how images are generated with text-to-image models. We observe that the iterative nature of generating images with diffusion models affords many opportunities for artistic decisions to influence the final media. This is shown to be true in prior projects [6, 7, 12], but these projects are primarily implemented in code, making their use opaque to average creative individuals. The goal of Noise Pilot is to provide an interface where artists can use text-to-image models to generate new types of images but at a level of abstraction that is available to them. Our tool provides a brush that affects diffusion in a way that artists can understand, manipulate, and improvise with, allowing for creations not previously possible.

Related Work

Creativity Support Tools

Creativity Support Tools (CSTs) are a type of computer interface that supports artistic efforts toward creative work. Shneiderman, in his eponymous article [17], outlines a number of important design principles for CSTs, such as supporting exploratory search and approachability for beginners but enough depth for experts. This work is grounded in Direct Manipulation Interfaces, a type of interface pioneered by Hutchins [9] as well as Shneiderman [16]. The principles of direct manipulation interfaces suggest building interactions that align closer to the semantic models of how a user formulates the actions they want to do to complete a task.

Modern perspectives on CSTs, such as by Li et al. [10] frame the design of these tools as a power dynamic that the tool creator exerts over the tool user by forcing them to formulate their creative ambition in the interactions supported by the tool. Li provides a helpful design space frame of vertical and lateral movement through creative work that CSTs should support.

Generative AI Tools

There have been a tidal wave of tools that claim to support creative work using generative AI. Perhaps the closest to our interface is ComfyUI [1], which is a similar node based graph editor for interaction with ML models. ComfyUI suffers from the same issues as many tools in this space which formulates many of the parameters and interactions in the colloquial framing of ML practitioners, which is often opaque and inaccessible to creatives.

A number of tools take an in-painting based approach of starting with a sketch and filling in the details via a diffusion model or GAN [3, 2]. Although these tools do allow users to manipulate pixels, similar to painting programs, they lack the ability for creatives to control the diffusion process itself. Put simply, models are still treated as black boxes that they can prompt engineer against.

Beyond The Prompt

Many projects have explored how to provide control over the diffusion process beyond prompt engineering.

Projects like Factorized Diffusion [6] and Visual Anagrams [7] have shown that predicted noise can be manipulated to constrain the denoising process beyond the capabilities of prompting. They produce a number of examples of images that embody creative ideation that is not achievable by prompting alone.

SDEdit [12] shows the strength of manipulating starting conditions for the iterative diffusion process. Their algorithm can produce in-painting examples and image to image translations using a simple trick of adding noise to an existing image and starting the iteration part way through the process. Other work in this space [11, 4, 18] explore the impact that starting noise conditions for diffusion have on the final image result, suggesting noise manipulation being important for generating the desired final image.

Our tool aims to allow artists to explore and play with all of these ideas in a more accessible medium.

Tool Design

We describe the design decisions that must be considered when building a tool to support more advanced creative control. The two most significant ways in which iterative denoising can be steered are by specifying the starting conditions and controlling how denoising occurs at each step. The design of the tool should allow users to make artistic decisions in both of these ways in order to develop new workflows for generating images.

Initial Conditions

The iteration process starts with a set of initial conditions. This is defined by a starting image and a starting iteration. If the starting iteration is 0, then the starting image is usually pure noise. Noise can be injected into an existing image, and the starting iteration can be increased to perform image-to-image translations. The outcomes of image-to-image translation look like the starting image but are manipulated by the prompt.

Noise has been shown to have a very large impact on the composition and content of the resulting image. Our tool should allow users to manipulate noise so they can establish the specific starting conditions that will lead to their desired image output. For instance, is it possible that taking a piece of noise from one starting condition and masking it into another will "copy" the object that is diffused in it's place to another image? These ideas should be explorable using the tool.

Iteration

At each step of the iterative denoise process, noise in an image is predicted and then subtracted from the image. Noise prediction is guided by a prompt, and can also be improved using techniques such as Classifier Free Guidance (CFG) [8].

As mentioned earlier, techniques presented in prior work [6, 7] have show the artistic benefits of noise manipulation during iterative diffusion. Our tool needs to support similar functionality to allow users to come up with their own constraints so they can guide the iteration process if it fits their artistic objectives.

Choice of Medium

We have established how controlling initial conditions and iteration during denoising are important for the final outcome, but how should we allow users to specify this? Considering that code is too low level for our target user base, and a fully instrumented interface is too high level, we look to interface modalities that allow code-like expression in visual forms.

Visual scripting languages have been shown to strike a good balance between writing code and expressability [19]. This seems like a good target level of abstraction for our tool.

Users will drag node objects into a canvas. Each node on the canvas can be hooked up to other nodes to specify how the data from one node flows into another. The composition of these nodes represents the composition of a computer program. Users will need to author programs for the initial conditions, and programs for the iteration stage.

The goal of this project is to study whether or not this is the correct choice of medium for this type of task.

Implementation

Here we describe how the previous design decisions are embodied in a research prototype, which we call Noise Pilot.

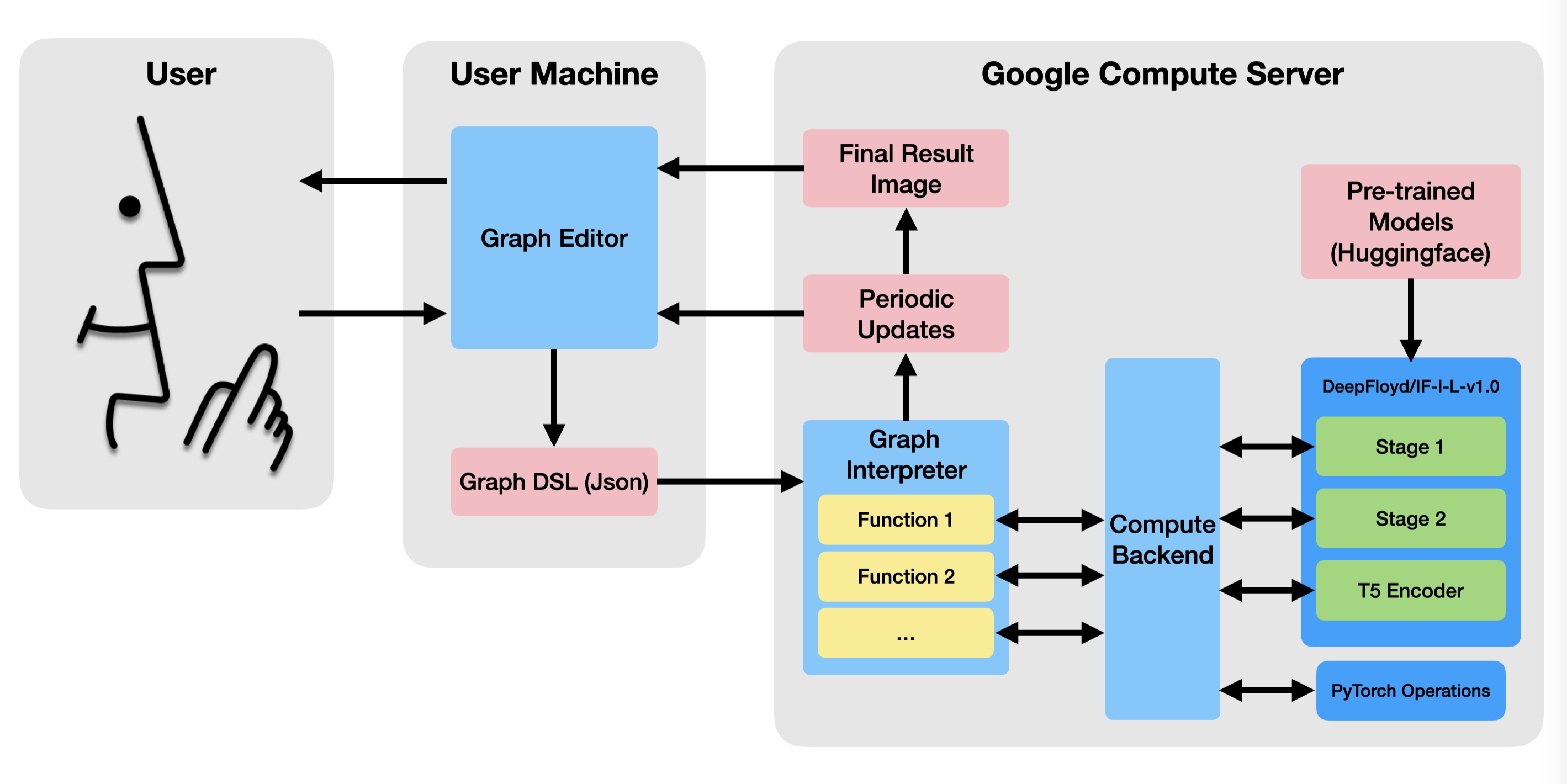

The system has two parts (See Figure 2). The client side application is the interface that the user interacts with, and is run within a web browser. The backend runs the programs specified in the front end, and calls the relevant machine learning and PyTorch functions.

Frontend Application

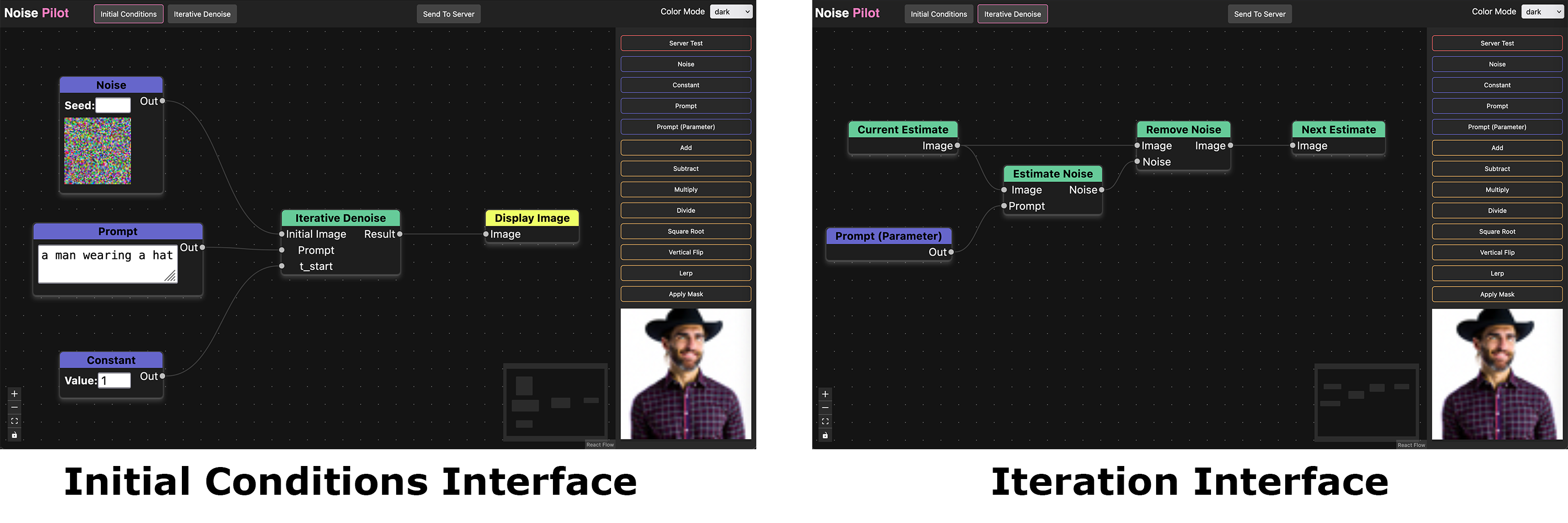

The front end is written in Typescript using the React interface library. It has two views, one to modify the initial conditions and one to modify the iteration steps. The user can toggle between these views with a button at the top of the screen.

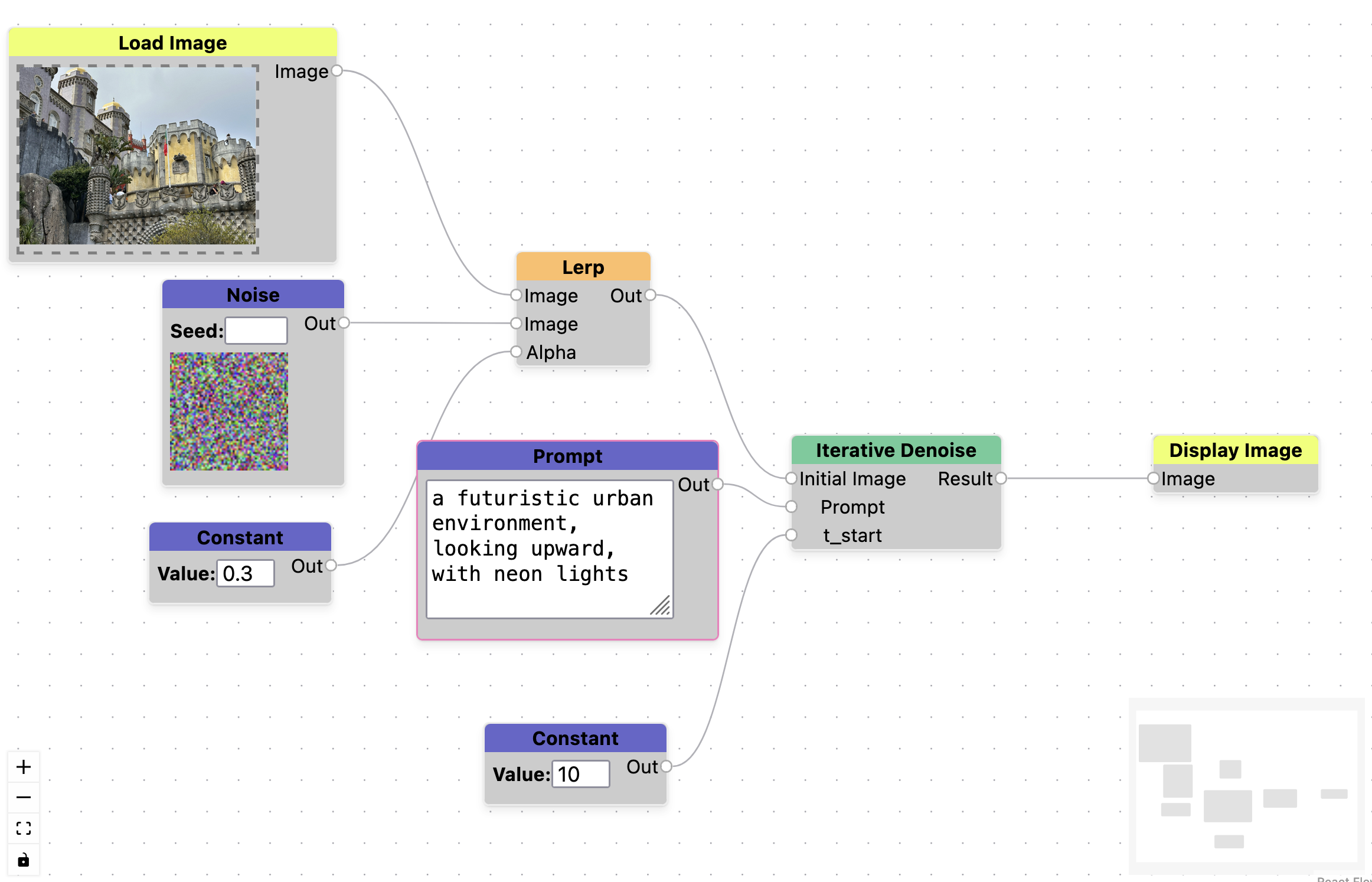

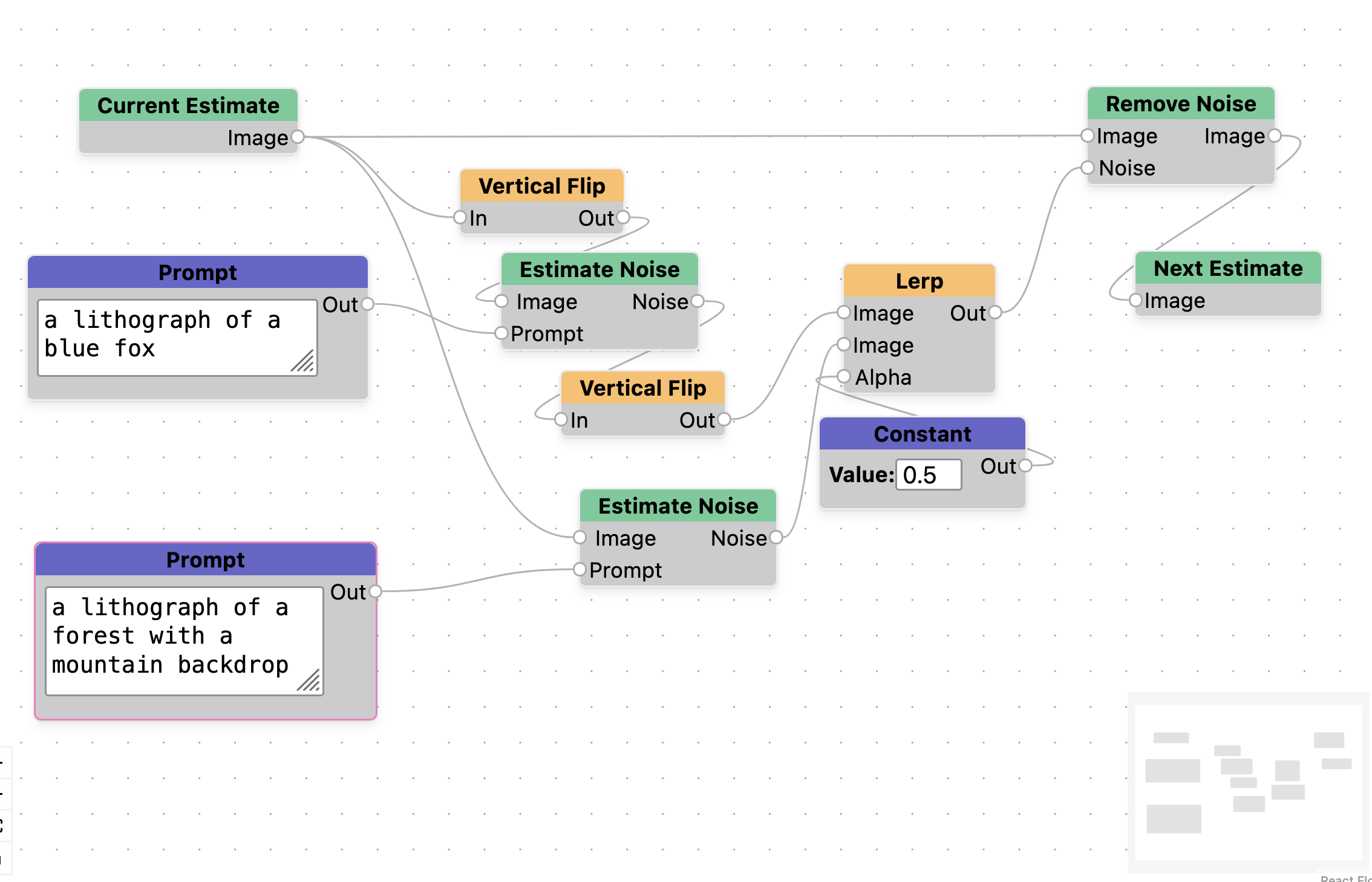

The iteration stage is treated as a node in the initial conditions graph (See Figure 1, left). This allows the user to pass in whatever data to the iteration step that they want, even allowing them to run the interation step multiple times with different sets of conditions. In each step of the iteration phase, the user should continuously set the next estimate of the iteration process (See Figure 1, right), although creative misuse of assumptions about what the next estimate should be should also be supported.

The node graph is then converted into a simple domain specific language defined by a Json file. The DSL contains a definition for each stage, and each definition is a list of nodes represented by their function name, and a list of edges describing how the nodes are connected. This json data is uploaded to a server where the actual computation of the graph happens. This is done with a button in the UI, and the intermediate and final results are displayed in the UI in the bottom right corner (Figure 1).

Backend Application

The backend runs on a Google Compute Server instance. It is written in Python using the Flask library to receive data from the client and send updates back to the client using Server Side Events (SSE). The backend consists of two major modules.

Graph Interpreter

The graph interpreter takes the graph program uploaded by the client and processes it one node at a time. The processing algorithm is simple: Given a node, look to see if it depends on the outputs of any nodes. If so, process those nodes. If not, run the function associated with the current node and store the results in a cache. If the current node depends on other nodes, find their results in the same cache.

Most of the functions are run on the compute backend, but the image loading and displaying functions are run within the graph processor itself. This is to encapsulate the backend from needing to do any file input/output tasks.

The graph processor is also responsible for keeping track of and updating the client on the current progress of the iterative denoising, sending regular image updates and percentage of the process completed. When the program is fully run, it sends a final output image to the client if the program requests one.

Compute Backend

The compute backend is essentially a shim layer that the graph processor can call into with a simple, consistent API. At startup it loads several ML models, such as DeepFloyd/IF-I-L-v1.0 (we currently only use the first stage of the model, but all stages can be used), and the T5 encoder for DeepFloyd to generate prompt embeddings.

The backend has several functions for controlling an iterative denoise loop, keeping track of the current image estimate and the current result/progress through the iteration. It also wraps several PyTorch operations suchs as torch.randn, torch.lerp, or TF.gaussian_blur.

Experiments

To determine the capability for the tool to create unique artistic outputs, we run a number of experiments on the initial condition and iteration stages that the tool supports.

Initial Conditions

First we test the ability of the tool to support inpainting. We accomplish this by creating a program that adds partial noise to an existing image (α=0.5), and then begins the diffusion process part way through (t_start=14). We test this on an image of Pena Castle taken in Portugal, and provide the prompt a futuristic urban environment, looking upward, with neon lights. The results can be found in 3. A screenshot of the graph used to generate these images is in the Appendix, Figure 9.

Figure 3. Inpainting example. Image (a) is a photograph taken of Pena Castle in Portugal. Image (b) is an image generated with the prompt a futuristic urban environment, looking upward, with neon lights, blended with 50% noise.

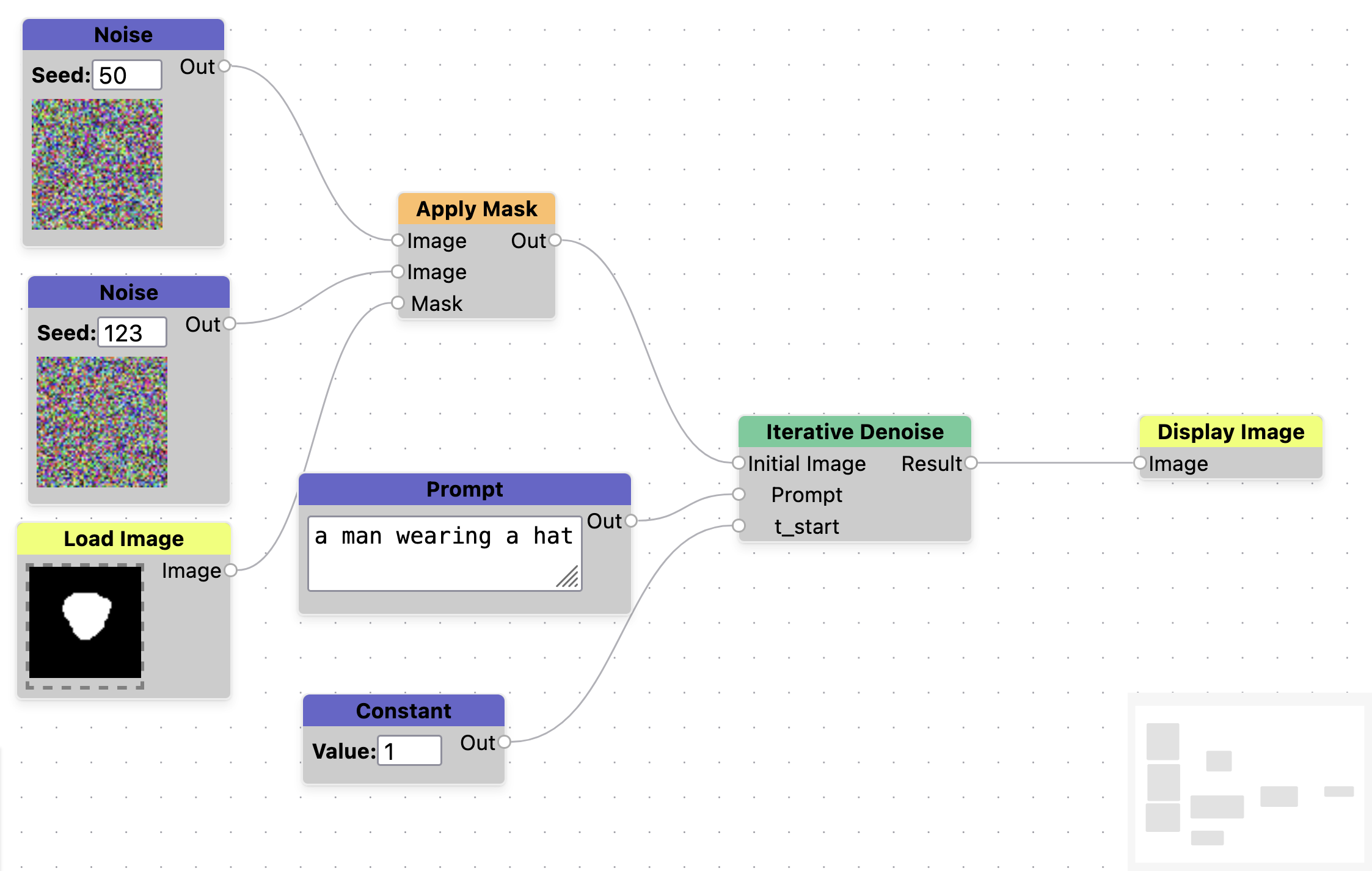

We also test the ability to manipulate noise in the initial conditions stage. On first instinct, if we generate an image from some noise with the prompt a man wearing a hat, and want to keep parts of that image, it should be possible to mask out that noise and fill in the rest with noise from a different image. We do this by taking noise images generated with seed=123, 50 and merge them using a mask. Where the mask pixels are white, we take pixels from seed=123, and where they are black we take pixels from seed=50. Figure 4 shows the results of this process, which are unsuccessful. What this implies is that the final image that gets produced is not based on each individual pixel value, but is based on some total influence of all of the noise in the image. See Appendix, Figure 10 for the graph used to generate this experiment.

Figure 4. Example of trying to use noise to paint features of one image into another. All images use the prompt a man wearing a hat. Image (a) was generated with noise seed=123. Image (b) represents a hand painted mask used to paint over the man's face. This is used to create a new noise image, where the white pixels are taken from seed=123 and the black pixels are taken from seed=50. Image (c) is the final output, and doesn't really resemble image (a).

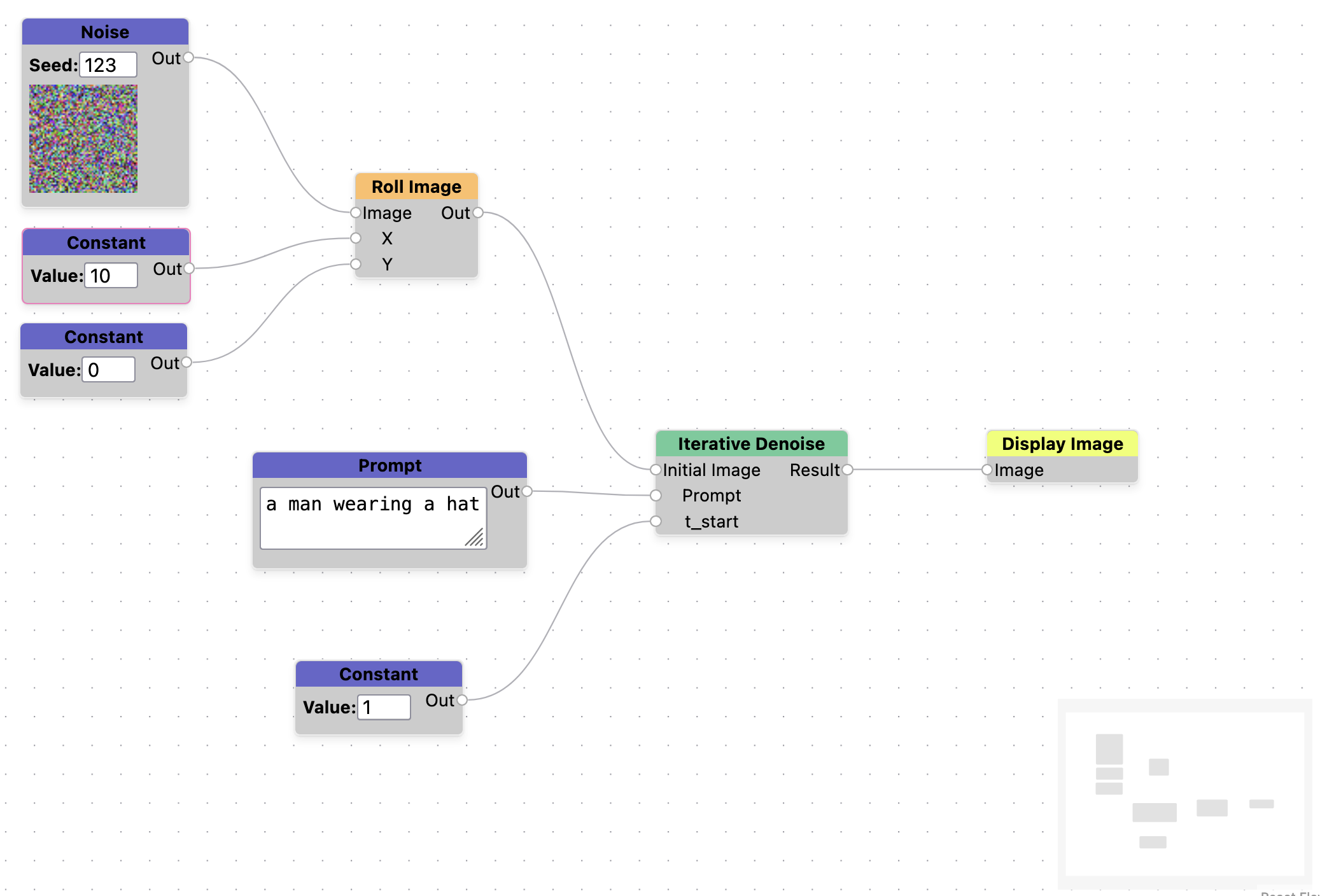

We can test this theory further, if the final image is based on the total noise in an image, we should be able to perturb the noise and see a similar looking image but it's unclear how similar it will be. Using the same prompt of a man wearing a hat, we generate 3 versions of the image with slightly offset noise in the x direction. We use values of x=0,3,5. We can see that the images generated greatly resemble the original image, but differ in some significant ways as well. This nudging of the noise could be a useful abstraction for the controlled generation of alternative images. See Appendix, Figure 11 for a screenshot of the graph used for this experiment.

Figure 5. Examples of perturbing noise in an image to generate similar images. All images were generated with the prompt a man wearing a hat with noise seed=123. Image (a) has no perturbation, image (b) is shifted by x=3 and image (c) is shifted by x=5 (nearly a 10% shift)

As a final experiment on initial conditions, we consider what happens when we start denoising some steps into the iterative diffusion process with no other changes. In this example we use a number of prompts to try to generate a rock wall with green moss in the cracks (Figure 6). The model struggles to output this image, mostly coloring all of the stones green. We observe that if we start the denoising process later (at t_start=7) that we can much more easily get the image content that we want. This represents an example of creative misuse of the medium - the medium is expressive enough that we can do the things in it that are necessary to get the results we want, even if that use is outside of the expected usage pattern of the tool designer.

Figure 6. Example of manipulating iteration parameters to achieve desired outputs. Image (a) was generated with the prompt a picture of a stone wall, close up face on. Image (b) was generated with the same prompt, appended by , with green moss in the cracks. Image (c) was generated by using the same prompt, but starting iteration at t_start=7.

Iteration

We also produce a test of whether the iteration part of the tool can produce novel images. In this case we produce a visual anagram like from Geng et al. [7]. We accomplish this by flipping the image before denoising, denoising with a different prompt, then flipping the noise estimate. For the example in Figure 7, we use the prompts a lithograph of a forest with a mountain backdrop and a lithograph of a blue fox. We can see that the foxes legs are reinterpreted to form the shape of the mountain. A screenshot of the graph used to generate this can be found in the Appendix, Figure 12.

Figure 7. Visual Anagram example generated by manipulating the iteration steps. Image (a) uses the prompt a lithograph of a forest with a mountain background. Image (b) uses the prompt a lithograph of a blue fox.

Proposed Study

The previous section shows that the tool is expressive enough to support artistic decision making in various ways, but the question still remains if the interface can support non-experts in creating their own unique visions. For this project we also propose a human factors experiment to be run sometime early next year.

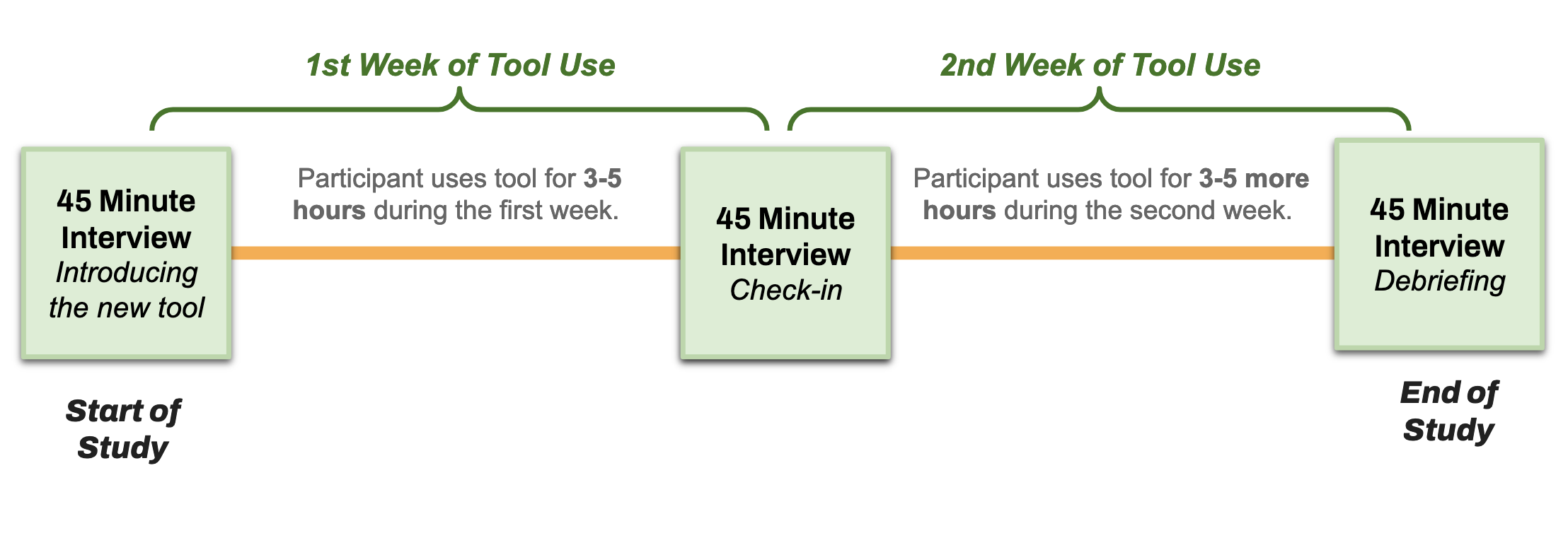

During recruitment we will select for artists that have some amount of technical skills. These might be shader artists, procedural artists, or artists that have some experience using existing diffusion based tools. The study will consist of a two week deployment (See Figure 8), where participants will be asked to use the tool for 3-5 hours per week. After the first week, we will conduct a check-in interview to solicit feedback about the tool and collect information on how they are progressing in learning how to use it. They will then spend another week using the tool, which will be followed up by another check in. We will also measure the ability for our tool to support creative work through survey instruments such as the Creativity Support Index [5].

Some of the research questions we are interested in by running this study are the following:

- Can artists learn to use an interface like this to control iterative diffusion? This question will answer if this choice of medium is the right one.

- Do artists have a better impression about generative AI if it is presented in a way that is more controllable by them? This question will answer if the form of the way they interact with generative AI affects their impression of the technology.

Future Work and Conclusion

Future work on this tool can begin by supporting more operations and iterative workflows. One such interaction we want to support in the future is to explore the relationship between output image and input noise. Would artists want to paint a mask directly over the output image to "capture" the noise at this points to use later? What interactions support this type of action? Additionally, future work can go into creating a more fully fleshed out set of node operations. Currently we only support a small subset of the torch api, but there are many more useful functions that could be included. Finally, in our own use of the tool, we've identified that being able to group a set of nodes as a sub routine would be a very useful tool operation.

We've shown that Noise Pilot has the ability to alter image outputs by performing operations on initial conditions and iteration steps. We've also embodied this ability in a tool that hopefully is more accessible to artists, and a planned human factors study will identify if this is the case. Our ultimate hope for this tool is not for it to become the de-facto diffusion manipulation tool, but instead to use it as an instrument to better understand how future generative AI workflows can be created to support artists.

References

- ComfyUI | Generate video, images, audio with AI. 2

- Draw Things: AI-assisted Image Generation. 2

- NVIDIA Canvas App: AI-Powered Painting. 2

- Donghoon Ahn, Jiwon Kang, Sanghyun Lee, Jaewon Min, Minjae Kim, Wooseok Jang, Hyoungwon Cho, Sayak Paul, SeonHwa Kim, Eunju Cha, Kyong Hwan Jin, and Seungry- ong Kim. A Noise is Worth Diffusion Guidance, Dec. 2024. arXiv:2412.03895 [cs]. 2

- Erin Cherry and Celine Latulipe. Quantifying the Creativity Support of Digital Tools through the Creativity Support In- dex. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact., 21(4):21:1–21:25, June 2014. 66

- Daniel Geng, Inbum Park, and Andrew Owens. Factorized Diffusion: Perceptual Illusions by Noise Decomposi- tion, Apr. 2024. arXiv:2404.11615. 2, 3

- Daniel Geng, Inbum Park, and Andrew Owens. Visual Anagrams: Generating Multi-View Optical Illusions with Diffu- sion Models, Apr. 2024. arXiv:2311.17919. 2, 3, 5

- Jonathan Ho and Tim Salimans. Classifier Free Diffusion Guidance, July 2022. arXiv:2207.12598 [cs]. 3

- Edwin L. Hutchins, James D. Hollan, and Donald A. Norman. Direct manipulation interfaces. Hum.-Comput. Inter- act., 1(4):311–338, Dec. 1985. 2

- Jingyi Li, Eric Rawn, Jacob Ritchie, Jasper Tran O’Leary, and Sean Follmer. Beyond the Artifact: Power as a Lens for Creativity Support Tools. In Proceedings of the 36th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technol- ogy, UIST ’23, pages 1–15, New York, NY, USA, Oct. 2023. Association for Computing Machinery. 2

- Shuangqi Li, Hieu Le, Jingyi Xu, and Mathieu Salzmann. Enhancing Compositional Text-to-Image Generation with Reliable Random Seeds, Dec. 2024. arXiv:2411.18810 [cs]. 2

- Chenlin Meng, Yutong He,Yang Song, Jiaming Song, Jiajun Song, Jiajun Wu, Jun-Yan Zhu, and Stefano Ermon. SDEdit: Guided Image Synthesis and Editing with Stochastic Differential Equations, Jan. 2022. arXiv:2108.01073. 2

- Dustin Podell, Zion English, Kyle Lacey, Andreas Blattmann, Tim Dockhorn, Jonas Mu ̈ller, Joe Penna, and Robin Rombach. SDXL: Improving Latent Diffusion Models for High-Resolution Image Synthesis, July 2023. arXiv:2307.01952 [cs]. 1

- Aditya Ramesh, Mikhail Pavlov, Gabriel Goh, Scott Gray, Chelsea Voss, Alec Radford, Mark Chen, and Ilya Sutskever. Zero-Shot Text-to-Image Generation, Feb. 2021. arXiv:2102.12092 [cs]. 1

- Eric Rawn, Jingyi Li, Eric Paulos, and Sarah E. Chasins. Understanding Version Control as Material Interaction with Quickpose. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI ’23, pages 1–18, New York, NY, USA, Apr. 2023. Association for Computing Machinery. 1

- Shneiderman. Direct Manipulation: A Step Beyond Pro- gramming Languages. Computer, 16(8):57–69, Aug. 1983. Conference Name: Computer. 2

- Ben Shneiderman. Creativity support tools: accelerating discovery and innovation. Communications of the ACM, 50(12):20–32, Dec. 2007. 2

- Ruoyu Wang, Huayang Huang, Ye Zhu, Olga Russakovsky, and Yu Wu. The Silent Prompt: Initial Noise as Implicit Guidance for Goal-Driven Image Generation, Dec. 2024. arXiv:2412.05101 [cs]. 2

- A.M. Winn and T.J. Smedley. Multimedia workshop: ex- ploring the benefits of a visual scripting language. In Pro- ceedings. 1998 IEEE Symposium on Visual Languages (Cat. No.98TB100254), pages 280–287, Sept. 1998. ISSN: 1049- 2615. 3

- J.D. Zamfirescu-Pereira, Richmond Y. Wong, Bjoern Hart- mann, and Qian Yang. Why Johnny Can’t Prompt: How Non-AI Experts Try (and Fail) to Design LLM Prompts. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI ’23, pages 1–21, New York, NY, USA, Apr. 2023. Association for Computing Machinery

Appendix